12/19/25

Context

Because I am a huge fantasy nerd, I studied the rhetorical history of Western dragons for my final project in a History of Rhetorical Theory class. Instead of writing a traditional formal academic essay, I chose the multimodal option, making an artwork that represents both medieval and modern interpretations of Western dragons.

Introduction

Dragons have been a universal symbol across time. The giant winged serpents inspired fear and power in many medieval Western cultures. There’s a gravity with dragons, a force that’s pulls our attention. Maybe it has something to do with the fire-breathing and general feeling of imminent death? Or maybe dragons mean more than their adversarial origins would lead us to believe. With so many historical and modern interpretations of dragons, you never really get tired of reading about them. It’s always fun to see how an author constructs their version of the beast. Dragons straddle a border between man and nature, and in spite of the passage of time, we keep coming back to the idea. Maybe we seek to understand what it means to overcome impossible odds, our own fears, or whatever else stands in the way of growing as a people. Or perhaps that impossibility is what fascinates us the most – a creature that feels so unreal yet was once thought to be as real as God. Here, we will explore what rhetorical purposes dragons serve in medieval and modern narratives and how they try to influence their audience.

Medieval Dragons

The medieval idea of a dragon is by far the most famous Western interpretation of the creature, and for a good reason. When the Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, the Christian church became the dominant power in Europe. As the word of God spread, so too did the idea of dragons. The idea of monstrous serpent-like creatures already existed in local legends and bestiary books in the land of the fallen empire. “According to Greek legend, dragons inhabited springs and occasionally rivers, which they guarded ferociously. This legend reached Europe in Roman times in a letter from Fermes… described a territory east of the Nile and Brixontes rivers, inhabited by dragons” (Lippincott). However, the Bible solidified defining characteristics of the Western idea of a dragon.

Several books of the Bible mention dragons or dragon-like creatures, some more notable examples are present in Job (describing the sea-dwelling Leviathan) and Revelation (describing Satan as a dragon) are listed below:

- “Who can open the doors of his face? His teeth are terrible round about. His scales are his pride, shut up together with a close seal.” ( Job 41:14-15 KJV)

- “His breath kindleth coals, And a flame goeth out of his mouth.” ( Job 41:21 KJV)

- “And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads.” (Revelation 12:3 KJV)

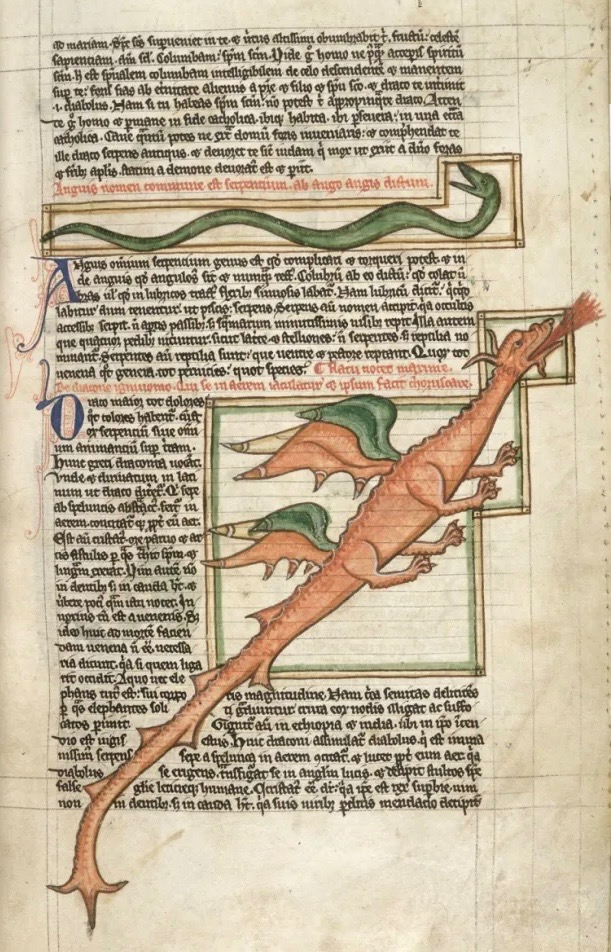

You can see the influence of draconic traits from the Bible in the MS Harley dragon as well as other artistic depictions of dragons during the period. In Christianity, dragons were used to show the power of God overcoming evil. A physical manifestation of evil aided the church’s ethos to convince citizens of the reality of God’s word. In rhetoric, ethos is when you make “appeals to audience values and authorial credibility/character” (Gagich).

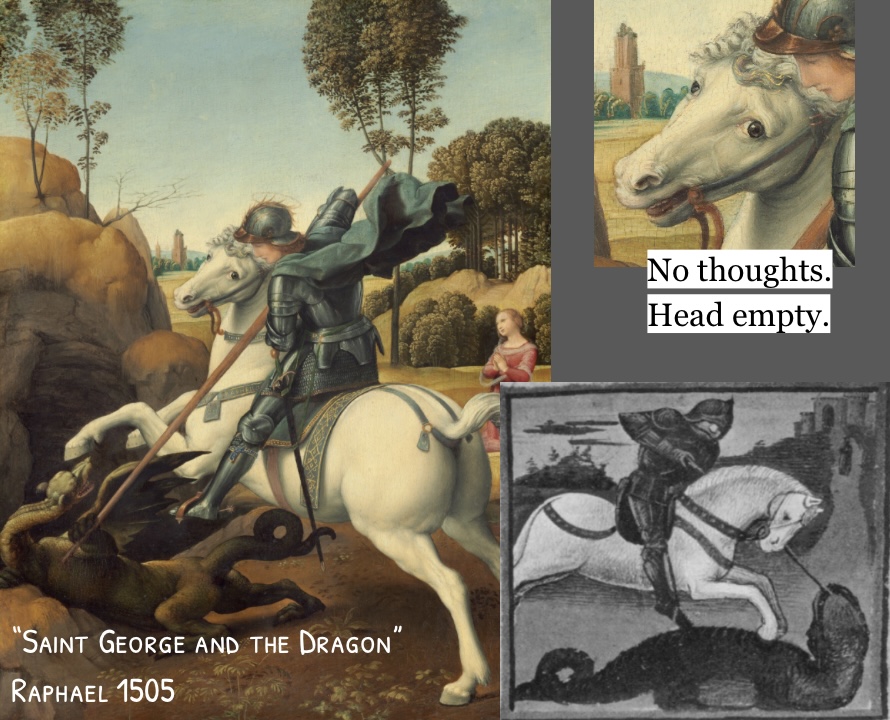

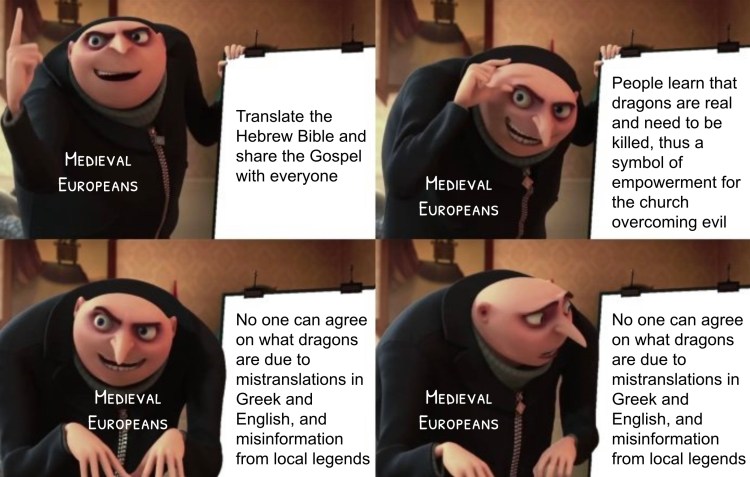

There were even those who claimed to have slain a dragon like Saint George in Catholicism, who was revered for his holy act. Despite George’s commendable intentions to conquer evil, it’s more likely that he conquered a common crocodile. It seems silly that George could mistake a crocodile for a dragon, but it didn’t help that biblical mistranslations led to misinformation about what dragons actually were:

- Dragons are mentioned frequently in Latin and vernacular Bibles, thanks to mistranslations of one Hebrew term signifying water monsters and another referring to a desert mammal now believed to be a jackal. Both creatures were rolled into one Latin term, Draco, which caused confusion and gave the dragon some contradictory characteristics” (Lippincott).

Even though Leviathan has what we would think of as draconic characteristics, the imagined Western idea of a dragon and the biblical truth of real dragons and other biblical beasts are very different. The diversity in interpretation is also partially due to lacking a unified system of knowledge since the remnants of the Roman Empire (the Holy Roman Empire aka The Byzantine Empire) only controlled the lands around the Mediterranean to the east (Britannica).

On top of that, many Europeans had never seen a crocodile on account of there being no Internet or crocodiles in medieval Europe. So when they saw the largest, scaliest, toothiest reptile they had ever seen in their entire lives, it’s understandable that they mistook the familiar U.S. Florida Gators mascot for evil incarnate. Sometimes, they would slay the beast, and take it back to the local church to display God’s victory in all its glory. Imagine sitting in the pew on Sunday and looking up at the dried-up carcass of ol’ Smiley chained up to the rafters as the choir sings.

That’s exactly what happened in Italy at Santuario Madonna Delle Lacrime Immacolate. It’s been there since at least 1534 AD when it was dated to have been removed from the church. . . only to later be found in the church’s attic during the 18th century (Cortesi). My question is, who loved this husk of a fake dragon so much that they secretly stashed it away in the attic?

Even with the Bible shaping the cultural consciousness on how we imagine dragons, mistranslations and local legends led to many different rhetorical interpretations. Dragons represented a didactic message (“intended for teaching or to teach a moral lesson”) of good conquering over evil (ccsoh.com). A real-life representation of Biblical creatures and displaying the dead carcass aided the ethos of the church. Dragons were portrayed as an antagonist force, which is a “character or force in a literary work that opposes the main character or protagonist” (Gagich). When the Renaissance came along, people tried looking for dragons again, yet couldn’t seem to find any nightmarish monsters that matched the old illustrations and descriptions.

- “Over time, so many fabulous traits accrued in the descriptions of these animals that by the Renaissance dragon descriptions strained credulity, and eighteenth-century scientists dismissed dragons as mythical” (Senter).

So it would seem the Western dragon’s story would end, fading into the past alongside the Roman Empire. Except the Roman Empire wasn’t dead yet! Well, not in spirit anyway. You see, heraldry (you know, like a coat of arms) was once a thing in Rome and had become all the rage during medieval times. Roman soldiers used to carry metal dragon heads with a cloth tail fixed to the end of long rods called Draconarius. “Noblemen, knights, and heralds may have fixed on the winged and legged image of the dragon for their blazons because of its resemblance to the dragons topping the standards carried by the Roman legions” (Lippincott). Seeing as it was already a precedent to appropriate the dragon for purposes besides religion like representing your country, heraldry literally carried the symbol of dragons into the modern age.

The City of London still has a pair of dragons on its Coat of Arms. England decided to set the standard for Western dragons being characterized by four legs, whereas a two legged dragon was defined as a wyvern (more on wyverns later) (Lippincott). The Red Dragon of Wales is represented on the country’s flag. And J.R.R. Tolkien never got over his obsession with Norse mythology.

Modern Dragons

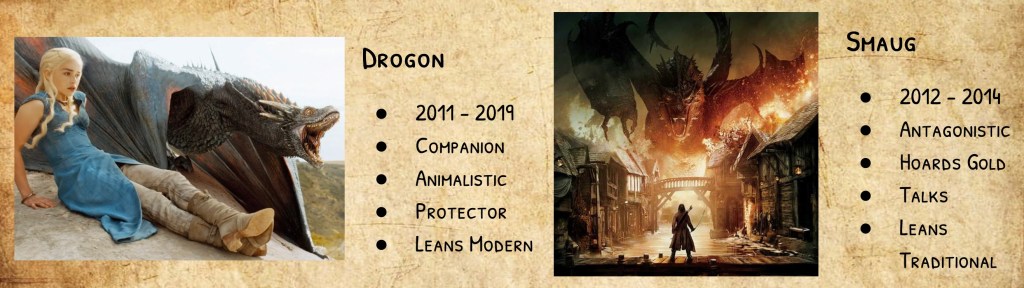

From here on out, we’ll be looking at some more familiar examples of dragons from the modern age (the past 87 years). Smaug the Terrible is the main antagonist of The Hobbit, a classic fantasy book written by Tolkien. Smaug sits on a pile of stolen gold, has lots of pointy teeth, loves gold more than anything, breathes fire, and hates it when people try to steal the gold he rightfully stole. Feels like a classic medieval dragon, right? Well, Smaug is unique among traditional dragons because he talks. He wasn’t the first dragon to talk in stories, but he is a famous example of early modern anthropomorphism with Western dragons. “Anthromorphism attributes human characteristics to nonhuman entities” (MasterClass). Smaug is definitely not a humane creature, but talking like a human is a step towards making dragons feel more like a reflection of our nature in addition to our imaginations.

Drogon is another famous dragon in literature and in television. He’s the companion of one of the main characters and aids her quest. The phenomenon of friendly dragons today can feel more like extensions of their human counterparts, almost like a pet. In addition to modern dragons appealing more to our sense of humanity, there’s also a desire to make them feel real. George R.R. Martin wrote about how he approached dragons in his A Song of Ice and Fire series. He writes in his Not a Blog: “I wanted my dragons to be as real and believable as such a creature could ever be… Four-legged dragons exist only in heraldry… Birds have two legs and two wings, bats the same, ditto pteranodons and other flying dinosaurs, etc” (Martin). Even though wyverns are distinct from dragons due to having two legs instead of four, by Martin’s standard, they are more realistic if you look at every other flying (non-insect) creature on earth.

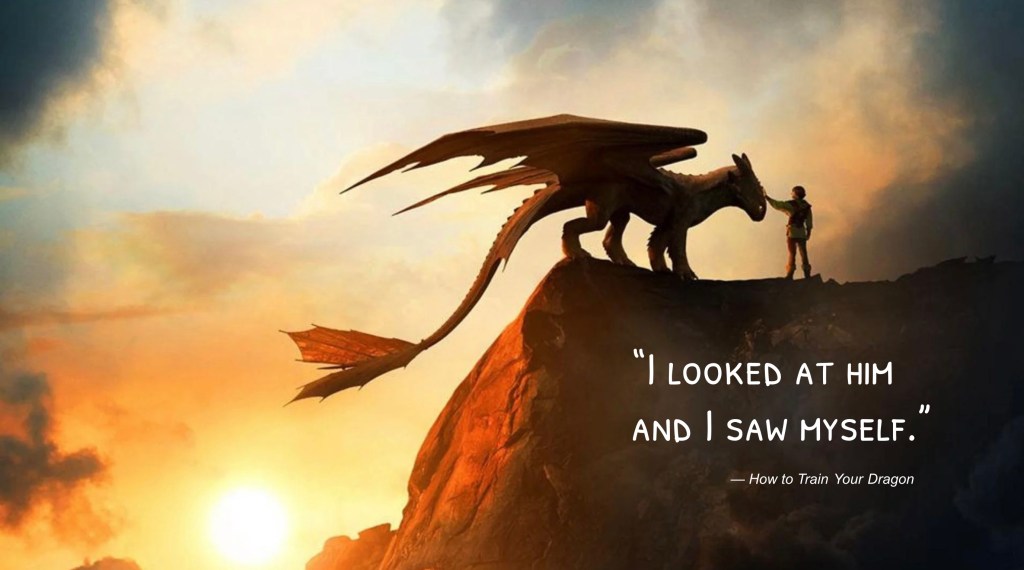

Realism is the “the literary practice of attempting to describe life and nature without idealization and with attention to detail” (ccsoh.us). The practice of realism appeals to the rhetorical element of logos which uses “logic, structure, and objective reasoning to appeal to an audience’s intellect” (Gagich). Even in stylized genres like the animated How To Train Your Dragon films, creating a dragon that feels like a living, breathing animal is the ultimate goal.

Leonardo Da Vinci once wrote: “You know that you can not make any animal without it having its limbs such that each bears some resemblance to that of some one of the other animals” Lippincott). Just like medieval artists who were tasked with representing real dragons, we task ourselves with creating life-like versions of our imagination. If we can’t find dragons in real life, why not make some ourselves? And why not appropriate a beloved creature for corporate branding?

While it has moved on from distinguishing soldiers on a battlefield, Heraldry is still alive today. Modern symbol use of dragons is used largely to represent fantasy, but it can also be used in other contexts. For example, the Seattle Sea Dragons football team use a dragon to represent strength in their team, and Dragonhead Radio in Wales references the cultural symbol of the Welsh dragon on the country’s flag. And, of course, Dragons continue to represent far away lands in the fantasy genre.

If you can think of a single creature that represents the whole of Western fantasy, it would be the Western dragon. Many authors have tried to harness the magical powers of inspiration from this legend. Some took that metaphor quite literally. The phenomenon of “dragon riding” was popularized by the Dragonriders of Pern fantasy book series. The Inheritance Cycle book series continued that trope. The How to Train Your Dragon animated and live action film series, in my opinion, has immortalized the idea of people riding dragons and dragons being our friends. Medieval dragons appealed to fear, but some modern dragons appeal to a pathos of friendship. Pathos is tapping into the audience’s emotions to get them to agree with the author’s claim” the claim here being that dragons don’t only represent fear (Gagich). How did this change of heart to dragons are friends not foes come about? Eastern dragons may play a part in that due to their helpful nature in Eastern legends. However, I needed to keep this solely focused on Western dragons or I was going to have way more fun researching than my college schedule would allow. A different explanation could be that this was a natural progression with Western dragons as we adopted their symbol and attributed human traits to them. They became more familiar, more personal. In Pern and Eragon, dragons aren’t animals; they’re another race of beings who think and feel just like us. Dragons represent our ultimate fantasy – to ride our wildest dreams and soar, fearlessly.

Conclusion

Western dragons are a perfect representation of fantasy as they are purely a product of the human imagination. Medieval dragons were grounded primarily in the Bible and regarded as antagonistic. Belief in them faded when imagination didn’t match reality, but fascination remained in the idea of fantastic, dangerous creatures. Dragons were then used to represent the ethos of people groups (company or country) and found a place in the fantasy genre in literature and visual mediums (especially when fantasy was obsessed with the medieval period… and still is in some ways). While dragons can still be portrayed as an antagonistic force today, they have been influenced by people anthropomorphizing dragons. Gradual experimentation and diversification of use has led to a broad range of interpretation. As much as they have changed, we still seek to make dragons that feel real.

Western dragons no longer only serve evil. They serve the human experience.

Artwork Symbolism

Note: In this section, I explain my process with making the artwork and how it represents my research visually. There’s no new info about Western dragons here, but if the artistic process interests you, then read away!

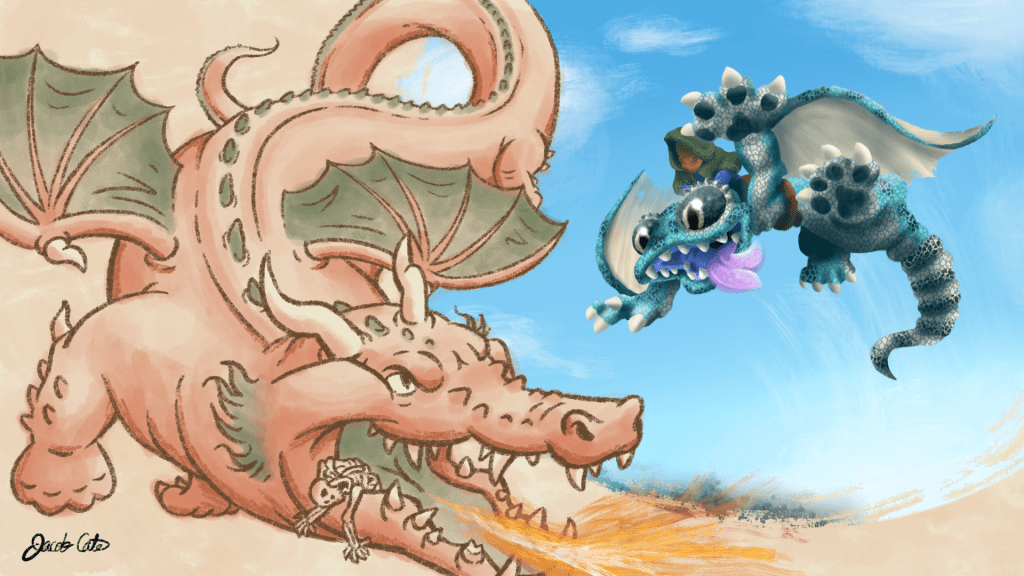

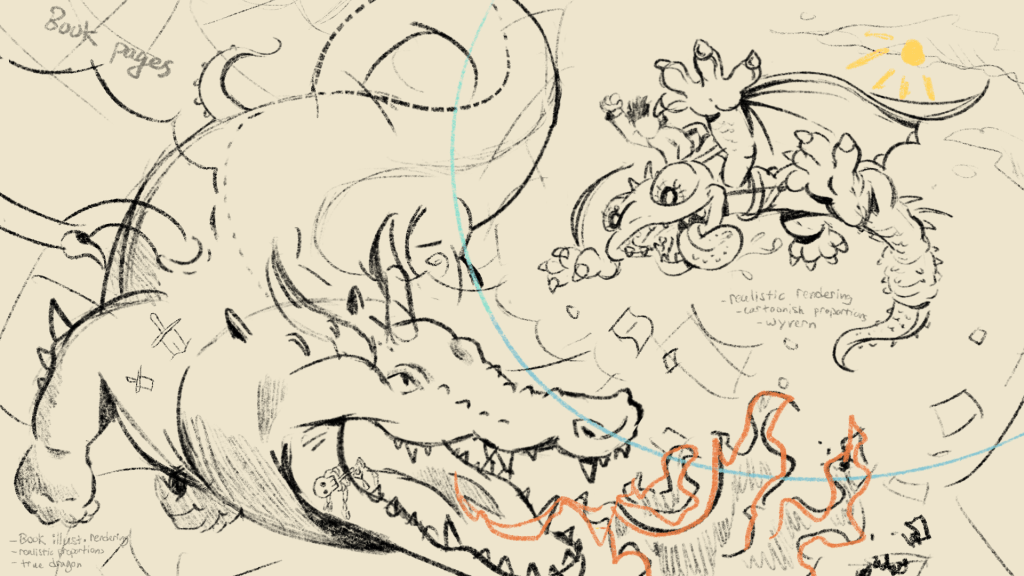

I started with the arrangement of what I knew had to be two dragons: one to represent the old medieval dragons and the other to represent the new modern dragons. Going off the rhetorical (and artistic) device of juxtaposition, I considered how I would want these dragons to interact. The first idea that came to mind was the Yin-Yang symbol. The line of rotating motion is felt through main curvature of the dragon spines and tails. It’s kind of ironic that I went with an Eastern arrangement to represent Western dragons, but it fits since Eastern dragons influenced the modern Western dragon. I couldn’t get the idea of dragons flying in a circle and facing each other out of my head, so that’s what I ended up going with. By facing each other, I don’t mean fighting… well, maybe they are fighting? It’s up to interpretation.

People and/or dragons who are facing each other face to face are generally implied to be antagonistic towards each other. However, the way I drew the dragons in Western Dragons Across Time doesn’t make their motivations entirely clear. There is definitely an interaction going on here, and while the Medieval Dragon looks like it means business with its fire-breathing and human skeleton hanging out of its mouth, the smaller Modern Dragon looks like it wants to play! The dragon rider’s obscured face hides any hint of motivation or attitude, thus leaving it to the audience’s interpretation.

Dragons aren’t just one thing and their definition is constantly changing. As George R.R. Martin points out in his blog post, he technically is writing about wyverns instead of traditional four-legged dragons in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Dragons can be both antagonistic and friendly. Highlighting both dispositions lends pathos in opposite directions, allowing the audience to lean more toward one or the other. The Yin-Yang arrangement also implies the ideas are in a cycle. The concept of a dragon and the roles they play is ever changing as the human imagination.

The dualism present in narrative roles and time is also present in the art style. The left side of the artwork is the past – the Medieval Dragon. The right side is the present – the Modern Dragon. The left side looks older and illustrative and the right is brighter and more realistic. The backgrounds represent the opposition through an old paper-like texture and open sky. Interestingly, the Medieval Dragon is burning the sky. I didn’t have any symbolism in mind when I drew that. I just thought it would look cool. It could be interpreted as the Medieval Dragon being the antagonist. For the Medieval Dragon’s style, I drew heavy inspiration from the earliest known picture of a dragon: MS Harley 3244. I noticed how the highlights were made from leaving negative space for the light page color to shine through, and the shading was made from darkening the red pigment. So, of course, the Medieval Dragon is red to call back to that classic red idea for a dragon that is also referenced Biblically. Instead of a little goatee, as is the usual staple for medieval dragons, I gave the Medieval Dragon hair on the side of the face (sideburns?) since the lower jaw was cut off by the end of the frame. I made parts of the Medieval Dragon go out of frame in order to emphasize the scale and intimidation, as if it is too big to fit into this picture. I wanted to include a reference to the “not-dragon” crocodiles found in some European churches. The body and head is based on the Nile crocodile since that was a type of crocodile in one of the churches. It has curved horns on its head, elbows, and wings to reference the slight curving horns in the MS Harley 3244. The didactic nature of dragons as an evil or opposing force in a narrative of good versus evil is represented by the Medieval Dragon due to its scale, threatening features, and deadly actions as seen through the skeleton and fire.

While modern dragons aren’t always friendly and cutesy, that particular depiction of dragons is a uniquely modern concept that appeals to pathos. Nevertheless, the Modern Dragon does retain a sense of power with its large claws upraised and ready to slash down at opponents… or perhaps it is flailing wildly in the air because it can’t contain its excitement? I prefer to interpret it as the latter! In order to differentiate the Modern Dragon from the Medieval Dragon, I needed to use a reptile as a reference that looked friendly. So I literally typed “friendly lizard” into Google and leopard geckos were one of the first search results. Leopard geckos have rounded, pudgy features with skinny legs. Perfectly non-threatening! Despite the cute disposition, a common trait in all dragons is power. I made the legs look more powerful in the Modern Dragon by slightly basing them off of snow leopards’ paws and giving the limbs more muscle. The wings are based on bat wings like the Medieval Dragon, but they kind of go their own direction. I wanted the wings to feel floppy and the ligaments in bat wings would make a wing more stable. So the wings end up looking more like sail-cloth, which is probably fitting imagery seeing as the dragon is a vehicle for the rider.

For this project, I attempted something in art that I never have before: realistic rendering. I’ve always been comfortable and more interested with drawing in a 2D cartoon style. However, for the Modern Dragon, lineart felt wrong to represent the realism and logos that is still a big trend in modern dragons on the big screen. So I removed the lines. Here’s what it looked like in the outline:

The Modern Dragon is a wyvern to show the progression toward modern dragons being represented in a two-legged wyvern fashion in order to project realism. The grin and tongue flailing out almost feels like a dog, showing the subservient nature of the dragon to the human (and also its playful personality which is related to anthropomorphism). Relating both dragons to real-life animal characteristics goes along with the Leonardo De Vinci quote about making imaginary animals believable by incorporating traits of real-life animals.

Last to examine is the dragon rider whose identity is a mystery. Hopefully, the character doesn’t come across as menacing with the shadowy hood. I wanted to obscure most of the facial features and color in order for the audience to self-insert themselves into the character (or at least, imagine who might be there). It doesn’t matter what gender or race the dragonrider is. The fun of dragons is how many ways people interpret them, so I didn’t want to nail down a specific type of person. The clothing didn’t feel quite right even after I shaded it until I added a simple white pattern around the edges of the hood. It looks like stitching and the result feels more like clothing instead of a blanket.

Postscript

Thanks so much for reading! I hope you enjoyed learning about Western dragons as much as I did. It took more time than expected to combine and both my essay and presentation into this article, but I’m proud of my work and I wanted it to live outside of the classroom.

Works Cited

For info about the Byzantine Empire: